FHIR 101: Basic Fundamentals

Resources, APIs and Terminology

Who Should Read This Guide:

Product Builders & Health Tech Innovators: You’ll learn how FHIR simplifies building healthcare apps and speeds up integrations.

Clinicians & Care Leaders: Understand how FHIR makes it easier to get complete, up-to-date patient information at the point of care.

Strategists & Policymakers: See how FHIR supports national goals for digital health, better access and secure data sharing.

Recap & What’s Next

Welcome to Part 2 of this guide! In this section, we’ll explore the foundational concepts you need to work with FHIR.

In Part 1 of the FHIR 101 guide, we explored existing legacy systems, why FHIR is essential to the evolving healthcare ecosystem and how national and global efforts are driving its adoption. If you haven’t read that section yet, be sure to catch up - FHIR 101: The Future of Healthcare Data Sharing.

What you will learn in this guide:

FHIR Resources

What are resources?

Resources are the building blocks of FHIR. Each resource holds specific healthcare info like patient details, allergies or medications in a consistent format.

What makes them powerful?

They are:

Easy to find and link together, much like pages on a well-organized website, with each resource assigned a unique web address (URL).

Customizable through “profiling,” allowing systems to request and share only the necessary data. For example: Requiring just the patient’s name and contact information to ensure accurate record matching.

Extensive and versatile, with HL7 defining hundreds of resources that cover nearly every healthcare scenario, making FHIR both flexible and comprehensive.

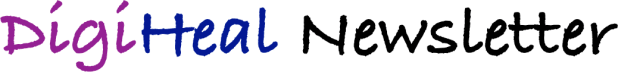

Example: Allergy to Penicillin

Every FHIR resource like “AllergyIntolerance” contains several key parts:

1. Resource Identity & Metadata

This section identifies what kind of resource this is and gives it a unique ID, like a passport number for this specific allergy record.

resourceType: Defines the type of data (e.g. AllergyIntolerance).

id: Unique identifier for this resource.

meta: Metadata such as version and last updated timestamp.

{

"resourceType": "AllergyIntolerance",

"id": "example-allergy-penicillin",

"meta": {

"versionId": "2",

"lastUpdated": "2025-06-25T12:00:00Z"

}

}It ensures every record is uniquely identifiable and traceable, so healthcare systems know exactly which data they’re working with and can reliably track updates.

2. Human-Readable Summary (Text)

A plain-language summary that can be read quickly by humans, like doctors and nurses.

status: Usually “generated,” meaning the system created this summary automatically.

div: The summary itself, wrapped in XHTML (a web-friendly markup language).

{

"text": {

"status": "generated",

"div": "<div xmlns=\"http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml\">John Doe is allergic to penicillin, causing a severe rash within 30 minutes of exposure.</div>"

}

}Special characters like < and > must be “escaped” as < and > in XML/XHTML to avoid errors. For example: The sentence - “If severity < moderate, then monitor.” should be written in code as -

<div xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

If severity < moderate, then monitor.

</div>3. Structured Data (Clinical Content)

This is the machine-readable heart of the resource, containing all detailed, coded clinical information software systems use.

clinicalStatus: Current status of the allergy (e.g. active).

verificationStatus: Confirmation level (e.g. confirmed).

code: The allergy itself, coded with standard medical vocabularies (e.g. RxNorm code “7980” for Penicillin).

reaction: Details about the allergic reaction, including manifestations (e.g. rash) and severity.

{

"clinicalStatus": {

"coding": [

{

"system": "http://terminology.hl7.org/CodeSystem/allergyintolerance-clinical",

"code": "active",

"display": "Active"

}

]

},

"verificationStatus": {

"coding": [

{

"system": "http://terminology.hl7.org/CodeSystem/allergyintolerance-verification",

"code": "confirmed",

"display": "Confirmed"

}

]

},

"code": {

"coding": [

{

"system": "http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/rxnorm",

"code": "7980",

"display": "Penicillin"

}

],

"text": "Penicillin"

},

"reaction": [

{

"manifestation": [

{

"coding": [

{

"system": "http://snomed.info/sct",

"code": "271807003",

"display": "Rash"

}

],

"text": "Severe rash"

}

],

"severity": "severe",

"onset": "2025-06-24T14:30:00Z",

"description": "Patient experienced rash 30 minutes after taking penicillin."

}

]

}4. Extensions

It allows adding custom information that doesn’t fit in standard fields, without breaking interoperability. Example: Additional notes reported by the patient about the timing of their allergic reaction.

Healthcare needs vary, so extensions let organizations customize data without losing compatibility like adding important footnotes in a contract.

[

{

"url": "http://example.org/fhir/StructureDefinition/allergy-notes",

"valueString": "Patient reported a full-body rash within 30 minutes of oral penicillin administration during outpatient treatment."

}

]5. References

FHIR resources often link to others to create a connected web of healthcare data.

patient: Reference to the patient associated with this allergy, linking to their patient record.

{

"patient": {

"reference": "Patient/example",

"display": "John Doe"

}

}RESTful API

How does FHIR use RESTful API?

Imagine you want to get or update healthcare info stored somewhere online (like a hospital’s computer system). FHIR uses REST API as the basis to help your computer or app talk to that system. It treats health data as resources like Patient details, Appointments, Medications or Lab Results.

Using REST API methods, apps can:

GET: “Show me the patient’s info.”

POST: “Add a new lab result.”

PUT: “Update the patient’s address.”

DELETE: “Remove an old appointment.”

Each request points to a specific URL endpoint (e.g. /Patient/123) and carries important info in headers (like who you are) and a body (the actual data).

What happens next?

When a FHIR server receives a request, it responds with the requested resource, usually in JSON or XML format. These responses often include hyperlinks to related data, enabling applications to easily navigate and retrieve connected records.

To make data sharing more efficient, FHIR groups multiple related resources such as a patient’s demographics, allergies, medications and lab results into a single package called a Bundle. Bundles help apps manage complex datasets by delivering all relevant information together in one response.

If REST isn’t enough ?

Some healthcare processes like referrals, prior authorizations or patient consent are too complex for simple REST calls. That’s why FHIR also supports:

Messaging (like secure emails or notifications)

Documents (like discharge summaries or clinical reports)

So, while REST is powerful and flexible, FHIR adapts to the real-world complexity of healthcare workflows.

If you’re interested in trying this out yourself, check out HAPI FHIR, a popular open-source RESTful FHIR server and testing tool. It’s a great way to practice what we’ve discussed and see FHIR in action.

Here’s a helpful guide to setting up a HAPI FHIR Server and a link to get started with testing REST APIs. Another useful resource to adopt FHIR - Open Health Stack.

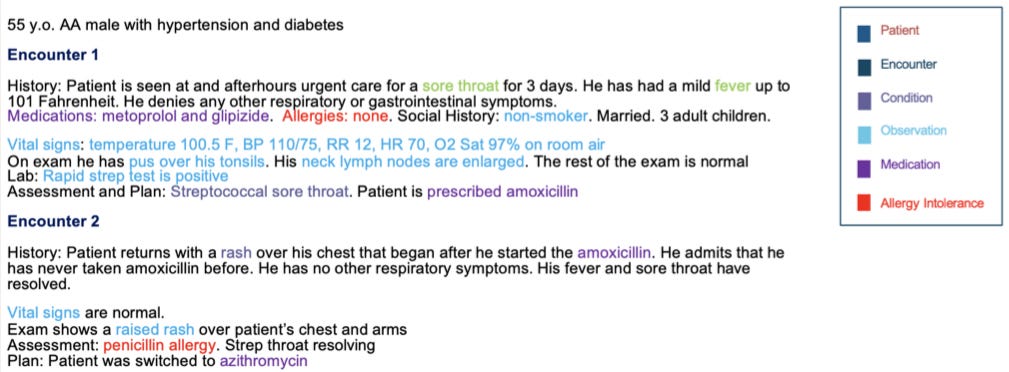

Understanding Terminologies in FHIR

What is Terminology in FHIR?

FHIR Terminology refers to the use of standardized codes and vocabularies inside FHIR resources to describe clinical concepts clearly and consistently like diagnoses, allergies, lab tests or medications.

Imagine one hospital calls “high blood pressure” by code X and another hospital uses code Y. Without a shared terminology system, software wouldn’t know these codes mean the same thing. This is where FHIR terminology helps ensure everyone “speaks the same language.”

This ensures:

Different systems understand the same meaning

Clinical data is interoperable and computable

Software can validate that the data uses approved and up-to-date terms

Terminology Components: Usage in an Allergy Resource

Let’s say a clinician is documenting a patient’s penicillin allergy. This data is captured using the AllergyIntolerance resource and here’s how standardized terminology is applied:

"code": {

"coding": [

{

"system": "http://snomed.info/sct",

"code": "300916003",

"display": "Allergy to penicillin"

}

],

"text": "Penicillin Allergy"

}Note:

"system" points to SNOMED CT, a globally recognized coding system.

"code" is 300916003, the SNOMED code for “Allergy to penicillin.”

"display" is the human-readable label.

"text" provides a plain-language summary, often for display in apps or patient portals.

Other components include:

Naming System identifies the code system (e.g. http://snomed.info/sct → SNOMED CT).

Code System defines the full set of concepts for a domain like drugs, observations or medical conditions (e.g. SNOMED CT concept for “Allergy to Penicillin” → Code 300916003).

Value Set limits which codes can be used in a specific situation (e.g. Value set of SNOMED CT codes for allergy types → 419199007 for Allergy of substance, 416098002 for Drug Allergy and 300916003 for Penicillin Allergy).

Concept Map translates codes across systems (e.g. SNOMED CT 300916003 → RxNorm 7980 for Penicillin G).

Now that we’ve explored how FHIR uses resources and standardized terminology, you might be wondering: When is this information actually exchanged between systems? Here is a helpful guide on FHIR data exchange.

How FHIR enables scalable Healthcare Innovation?

Product Builders & Health Tech Innovators

Problem: Legacy healthcare systems don’t easily share data and are slow to connect with new apps.

Solution: FHIR lets developers quickly build apps that work across many healthcare systems.

Use Cases:

Personal Health Records / Patient Access Apps: Hospitals open their systems so patients can safely see their health info online, like lab results and medical documents.

Unified Patient Records: Apps collect medical data from different hospitals to create one complete timeline for the patient.

Telehealth: Video call with doctor shows important patient info like medications and test results during the session.

Rural Clinic Integration: Small clinics can easily share lab tests and referrals with big hospitals.

Consent Management: Tools read notes to check if patients agreed to be contacted by phone or email.

Real-Time Insurance & Claims: Apps instantly check if insurance is active and show claim updates to patients and doctors.

Offline Care & Social Needs: Apps work even without internet and help doctors understand social issues like food insecurity.

Microservices for Appointments: Small software parts help manage patient registration and scheduling, making hospital systems easier to update.

Clinicians & Care Leaders

Problem: Patient info is scattered across many systems, causing delays and errors.

Solution: FHIR brings labs, images, notes and care plans together in one easy-to-use view.

Use Cases

Quick Access to Test Results: Doctors get labs and images in one place during visits.

Real-time Care Coordination: Different doctors and care teams update patient plans together in real time.

Automatic Record Retrieval: Patient histories load automatically without staff making phone calls or sending faxes.

Clinical Decision Support: Doctors get alerts, like warnings about drug interactions, during care.

Allergy Alerts: Systems show clear warnings to avoid giving medicines patients are allergic to, enhancing patient safety during treatment.

Strategists & Policy Makers

Problem: Older systems can’t easily provide real-time data or help reach all communities.

Solution: FHIR helps securely share data, support public health and improve equitable care.

Use Cases

Secure Data & Document Sharing: Share medical images, audio recordings and signed consent forms safely.

Public Health Reporting: Track disease outbreaks and vaccination data quickly.

Automated Quality Reporting: Use measures like HEDIS to check hospital care quality faster and more accurately.

Social Needs Integration: Connect clinics with housing, food and transportation services to support patients better.

Care Team & Payer Collaboration: Help multiple care teams and insurance providers work together smoothly.

Clinical Research: Share patient data to speed up medical studies and trials.

Genomics & Precision Medicine: Add genetic information to patient records for personalized treatments.

Coming Up Next

We’re shifting gears from health systems to personalized, tech-driven care. In our next edition, we’ll kick off a new series on at-home diagnostic wearables and kits. From emerging technologies to transformative care models, we’ll explore how home-based care is driving better outcomes. Stay tuned!